Historians are rediscovering one of the most important LGBTQ activists of the early 20th Century – an Asian Canadian named Li Shiu Tong. You probably don’t know the name, but he was at the center of the first wave of gay politics.

Much has been written about Li’s older boyfriend, Magnus Hirschfeld. Hirschfeld was a closeted German doctor and sexologist who became famous in the 1930s as a defender of gay people. In books on Hirschfeld, Li is usually just a footnote.

But as I found in my research, Li was a sexologist and activist in his own right. And in my view, his ideas about sexuality speak to our moment better than his much more well-known boyfriend’s do.

When Li died in Vancouver in 1993, his unpublished manuscript about sexuality was thrown in the trash. Luckily, it was rescued by a curious neighbor and eventually ended up in an archive. Since then, only a handful of people, myself included, have read it.

In its pages is a theory of LGBTQ people as the majority that would resonate with a lot of young people today.

Student and mentor

Born in 1907 in Hong Kong, Li was a 24-year-old studying medicine at a university in Shanghai when he met Hirschfeld. Hirschfeld, then 63 years old, had come to China to give public lectures about the science of sex. The year was 1931.

The Shanghai newspapers billed Hirschfeld as the world’s foremost expert on sexuality. Li must have seen the papers, because he made sure to catch Hirschfeld’s very first lecture. In medical school, Li had read all he could about homosexuality, then a very controversial topic. He had often encountered Hirschfeld’s name, and he knew his reputation as a defender of homosexuals. Whether he suspected that the famous sexologist was gay is a mystery. Almost no one in the 1930s could afford to be out – it would have destroyed either man’s career.

Magnus Hirschfeld and Li Shiu Tong appear on a 1933 issue of the French magazine Viola.

GLBT Historical Society

The lecture that afternoon was hosted by a Chinese feminist club at a fancy, modern apartment building. When Hirschfeld finished speaking, Li came up and introduced himself. He offered to be his assistant. It was the beginning of a relationship that would profoundly shape gay history, as well as the rest of both of their lives.

With Li by his side, Hirschfeld spoke all over China. Li then accompanied Hirschfeld on a lecture tour around the world, traveling first class on ships to Indonesia, the Philippines, South Asia, Egypt and beyond.

In his lectures, Hirschfeld explained his influential model of homosexuality: It was a character trait that people were born with, a part of their nature. It was neither an illness nor a sin, and the persecution of homosexuality was unjust. He gave 178 lectures, plus radio interviews. His ideas reached hundreds of thousands of people.

This was the first time in world history that anyone told so many people that being gay was not a bad thing and was, in fact, an inborn and natural condition.

A love affair and professional collaboration

On the world tour, the two fell in love, though to everyone else, they passed as teacher and student. Hirschfeld decided to make Li his successor. The plan was for Li to return to Berlin with him, train at his Institute for Sexual Science and carry on his research after his death.

Their shared dream was not to be. When they reached Europe, Hirschfeld realized he could never go back to his home in Berlin. Hitler was chancellor. The Nazis were after Hirschfeld because he was Jewish and because of his left-wing views on sexuality. He went into exile in France.

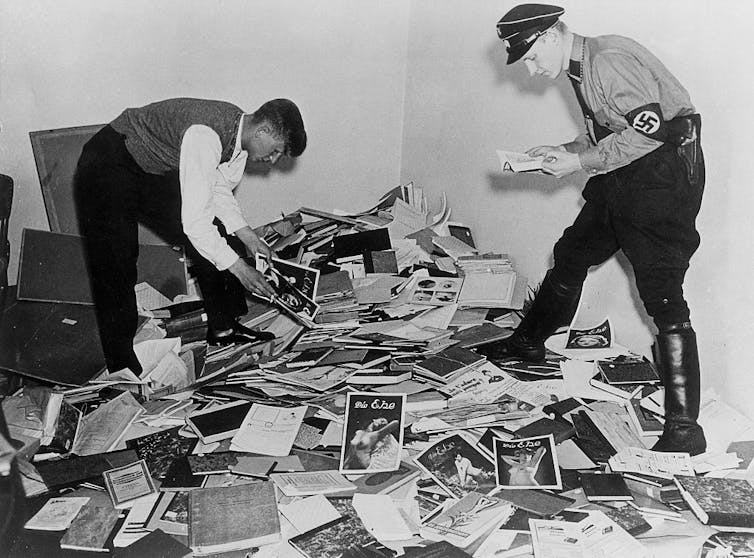

Nazis select books for burning at the Magnus Hirschfeld Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin.

ullstein bild/Getty Images

Li stayed by his side and helped him write a memoir of their travels.

It is a stunning departure from Hirschfeld’s earlier work, which trades in racist thinking – containing, for example, the claim that Black Americans had stunted brains.

In the book he wrote with Li’s help, a different Hirschfeld emerges. The text denounces imperialism – for example, calling British rule in South Asia “one of the greatest political injustices in all of the world.” Hirschfeld even saw a link between gay rights and the struggle against imperialism: both grew out of an undeniable human yearning for freedom.

After Hirschfeld died in France in 1935, his will named Li, then a student at the University of Zurich, his intellectual heir.

Hirschfeld was the most famous defender of gay people the world had yet known. But when Li died in Vancouver in 1993, it seems no one realized his connection to gay rights.

Li’s vision of sexuality reemerges

Yet Li’s rediscovered manuscript shows he did become a sexologist, even though he never published his findings.

In his manuscript, Li tells how after Hirschfeld died, he spent decades traveling the world, carrying on the research and taking detailed notes while living in Zurich, Hong Kong and then Vancouver.

The data he gathered would have startled Hirschfeld. 40% of people were bisexual, he wrote, 20% were homosexual and only 30% percent were heterosexual. (The last 10% were “other.”) Being trans was an important, beneficial part of the human experience, he added.

Li Shiu Tong at the 1932 conference for the World League for Sexual Reform.

Wellcome Images/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Hirschfeld thought bisexuals were scarce and that even homosexuals were only a minor slice of the population – a “sexual minority.” To Li, bisexuals plus homosexuals were the majority. It was lifelong heterosexuals who were rare – so rare, he wrote, that they “should be classified as an endangered species.” Li found same-sex desire to be even more common than had sexologist Alfred Kinsey, whose studies identified widespread bisexuality.

Recent polling finds LGBTQ-identifying people at lower percentages, but it also points to the numbers rising. According to a Feburary 2022 Gallup poll, they’ve doubled over the last ten years. That same poll found that almost 21% of Gen Z Americans – people born between 1997 and 2003 – identify as LGBTQ.

Some critics have suggested that these numbers reflect a fad. That’s the explanation given by the pollster whose very small survey found that about 40% of Gen Z respondents were LGBTQ.

Li’s vision conveys a more likely explaination: Same-sex desire is a very common part of human experience across history. Like Hirschfeld argued, it is natural. Unlike what he thought, however, it is not unusual. When Li was a young man in the 1930s, there was a very strong pressure not to act on same-sex desires. As that pressure lessened across the 20th century, more and more people seem to have embraced LGBTQ identities.

Why didn’t Li publish his work? I’m not sure. Perhaps he hesitated because his findings were so different from his mentor’s. In my book, I investigate another possibility: how the racism in Hirschfeld’s earlier work may have dissuaded Li from carrying on his legacy.

Yet Li’s theory was ahead of his time. A queer Asian Canadian at the heart of early gay politics, a sexologist with an expansive view of queerness and transness, he is a gay hero worth rediscovering.